Artists have a terrible reputation. I find it kind of insulting, but on the other hand I can understand where it comes from.

Artists have a terrible reputation. I find it kind of insulting, but on the other hand I can understand where it comes from.

Almost my entire family and most of my friends are deeply technical, scientific, quantitative people. And I’m an artist. These people don’t think less of me for my choice of field, but there is an attitude in the sciences that the arts are just easier than technical work. That has been a big challenge in my life. And recently there’s been a study with the fairly obvious result that people drop out of math and science majors because they’re hard. And a lot of them wind up in the arts.

The study talks a lot about the “sink or swim” aspect of freshman year in technical fields. These people are taking brutal introductory courses in math, physics, computer science, and more, and if they aren’t well enough prepared, or if they don’t do well in all of them, they’re pushed out of the major. It’s a harsh way of cutting away the dead wood, and it’s certainly not a perfect way of doing it, but people who do survive the sink-or-swim treatment have in a real sense proven themselves.

So the math and science people who make it through this grueling treatment see their ‘lesser’ colleagues flee to the safe waters of the humanities. Then the technical people conclude that what I do is really easy, and the people who do it aren’t terribly clever, because the people they see going into it are distinguished only by their ‘failure’ in a technical field. Sometimes it’s an explicit prejudice, but at least in my life it’s mostly a background attitude that’s hard to pin down and hard to combat directly.

Of course I myself believe that what I do is supremely challenging and rewarding. Doing what I do at the highest level requires just as much intelligence and talent as doing math, science or engineering at the highest level. But I also understand where this attitude about artists comes from.

Excellence is Always Hard

It isn’t easier to excel in the arts than in the sciences. It’s harder to fail as a student. The arts and the humanities don’t have the same mechanisms for pushing people out of the field. There are a lot of reasons for this.

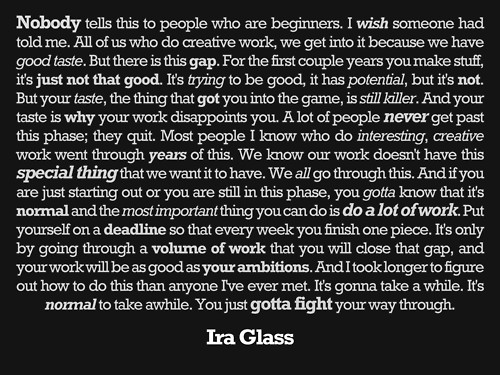

If you’re writing a poem in college, even if you have incredible potential and talent, odds are that your writing isn’t very good yet (see the Ira Glass quote above). Playwrights and composers in particular can count as ‘young’ or ’emerging’ until their mid-40s. For a point of contrast, you can’t win the Fields medal, the highest award in mathematics, after the age of 40. But as a student artist you’re indistinguishable from all the other students, some of whom are brilliant and some of whom fled physics.

The nature of the endeavor is just such that it’s basically impossible to tell the wheat from the chaff at this point. So if you’re chaff, you’ll probably flee the hard sciences for the arts when you hit college, if you haven’t already. That does fill the arts majors with less talented people, but it doesn’t make being a great artist any easier than being a great scientist.

It’s worth pointing out something about university training vs. the job market in the arts vs. the sciences. If you think the freshman year technical courses are sink or swim, try spending your twenties eating ramen and writing poems waiting for $250 to come in the mail for a poem printed in the New Yorker. Then tell me about sink-or-swim. Neither of these systems is a good idea, but the idea that artists have it easy because they don’t flunk out of school enough is just silly.

Personally…

For me, the arts are a more exciting challenge than the sciences. In technical fields, you can tell if it works or if it doesn’t. You can test one variable at a time. The machine you’re building has parts and you can take it apart, check it, and put it back together again. On that side of the fence, Life Makes Sense.

In the arts you can try to do that. God knows I spend a lot of time studying my pieces to see if they really work. But it’s not a clear process. If I’ve got a marimba player on the stage and the lights a certain way and the costume a certain way and one character is moving upstage while another delivers a line, and I’ve picked the notes the marimba player is playing… does that work? Does it move you?

I can kind of tell. But I’m trying to test whether or not a fiendishly complex machine (the piece of working theater) will or won’t elicit a fiendishly complex emotional reaction in you, my audience. I love finding real data to show whether or not it worked, but there’s barely any of that to be found. And there certainly aren’t any controlled experiments. I can’t have a control group that isn’t going to see a play and test group that is. I can’t tell my actors to give a lackluster performance one night and their A-game the next. Also, you, the audience, might be hungry, or tired, or cold, or if this is the Edinburgh Fringe, usually damp.

So I’ve got to build rather unscientific tools to make my decisions, study the problem, and then try my best to make something magical. It absolutely doesn’t make sense. But sometimes it works, and a roomful of people feel something they’ll never forget. And you’ll never understand how it worked.

That’s what makes art so exciting. That’s what makes it so challenging. Remember that the next time one of your relatives picks a field with no job prospects.

Late Update: After I posted this, there was some great discussion on Facebook, including some really good criticism that I completely agreed with. I wrote up the critiques over here.